GCC not at risk of food insecurity but inflation as Ukraine crisis disrupts supply

Follow-ups -eshrag News:

RIYADH: The ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine is creating major disruptions in global food supplies, creating fear of food insecurity and inflation in some countries heavily reliant on imports amidst rising energy costs.

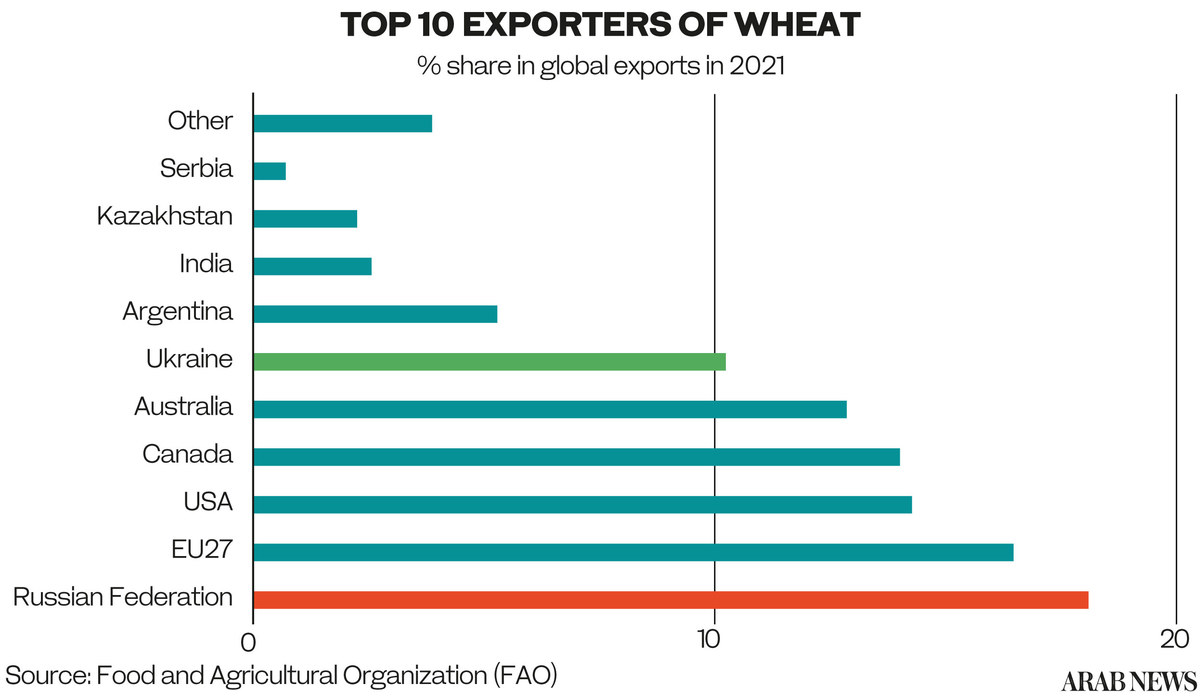

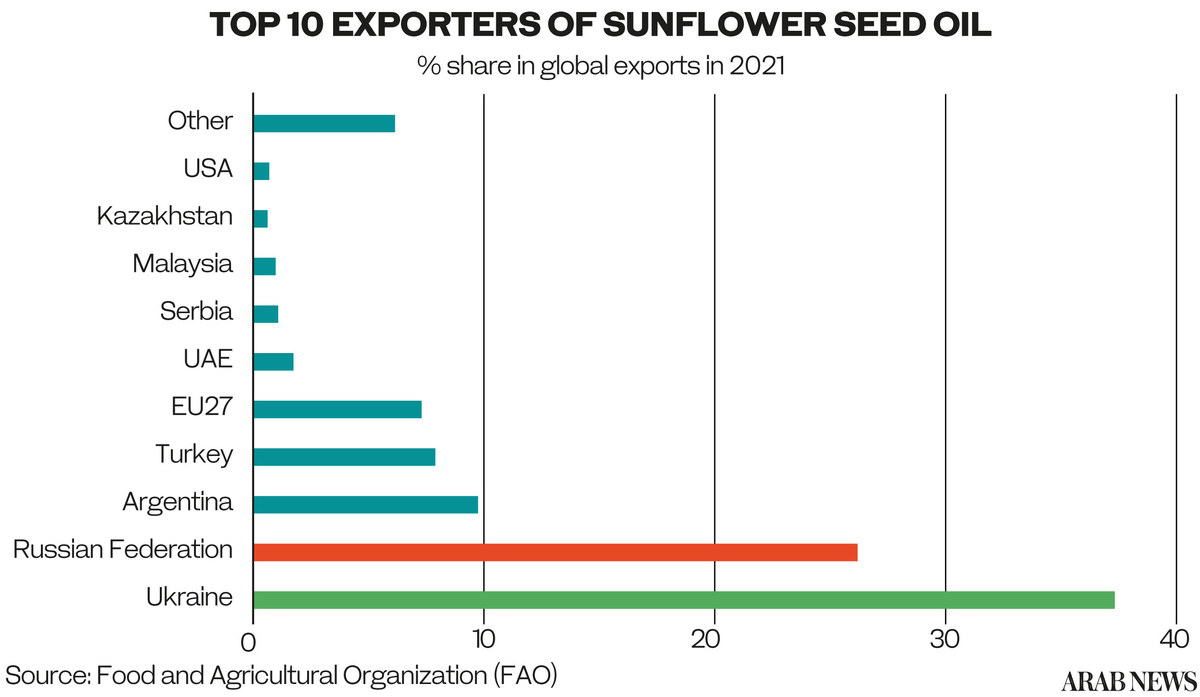

The two countries ranked among the top three global exporters of wheat, maize and sunflower oil, among others, according to a new paper by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, or FAO.

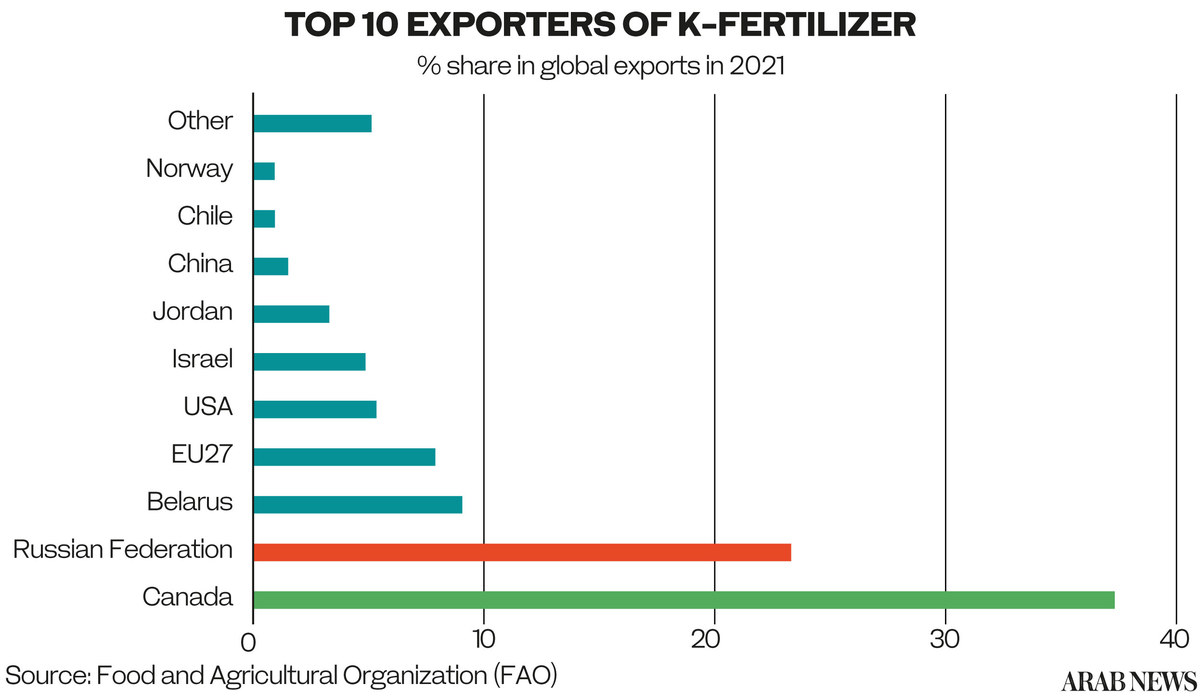

In addition, Russia is also one of the leading exporters of fertilizer, an essential material used in the farming business.

These disruptions, combined with rising transportation costs due to energy prices hikes, could lead to food insecurity for many countries in the Arab region.

“With the Ukraine crisis, we are getting challenged by constant changes in the availability of raw material used in finished (food) products,” said Sasha Marashlian, managing director of Imagine FMCG, an international distributor covering the GCC markets.

He said that countries exporting food commodities are now blocking or capping raw material exports. “This is translating into a lack of availability of certain products and a massive hike in food pricing due to supply and demand dynamics.”

“In my opinion, every food product will be impacted,” he added, underscoring that food prices could rise by 17 to 20 percent over the next 18 months in the GCC.

Food protectionism

As food protectionism is spreading, many countries have begun to halt the export of essential food items to secure domestic supply amid rising global supply chain concerns.

On March 14, for instance, Russia temporarily banned grain exports to ex-Soviet countries and most of its sugar exports. This came on the back of Hungary deciding to ban grain exports on March 5. Egypt followed suit by banning exports of strategic commodities for three months, namely lentils and beans, wheat, and all kinds of flour and pasta.

Food-producing countries are using export bans to preserve stocks of essential commodities amid what is turning into a severe global crisis.

Rising fuel prices are worsening the situation, leading to higher transportation and freight costs. “Shipment costs are now four to five times compared to two years ago, and the freight cost is at its highest ever,” pointed out Marashlian.

The international distributor believes that the impact will be fully priced in, after Ramadan, once local safety stocks start depleting.

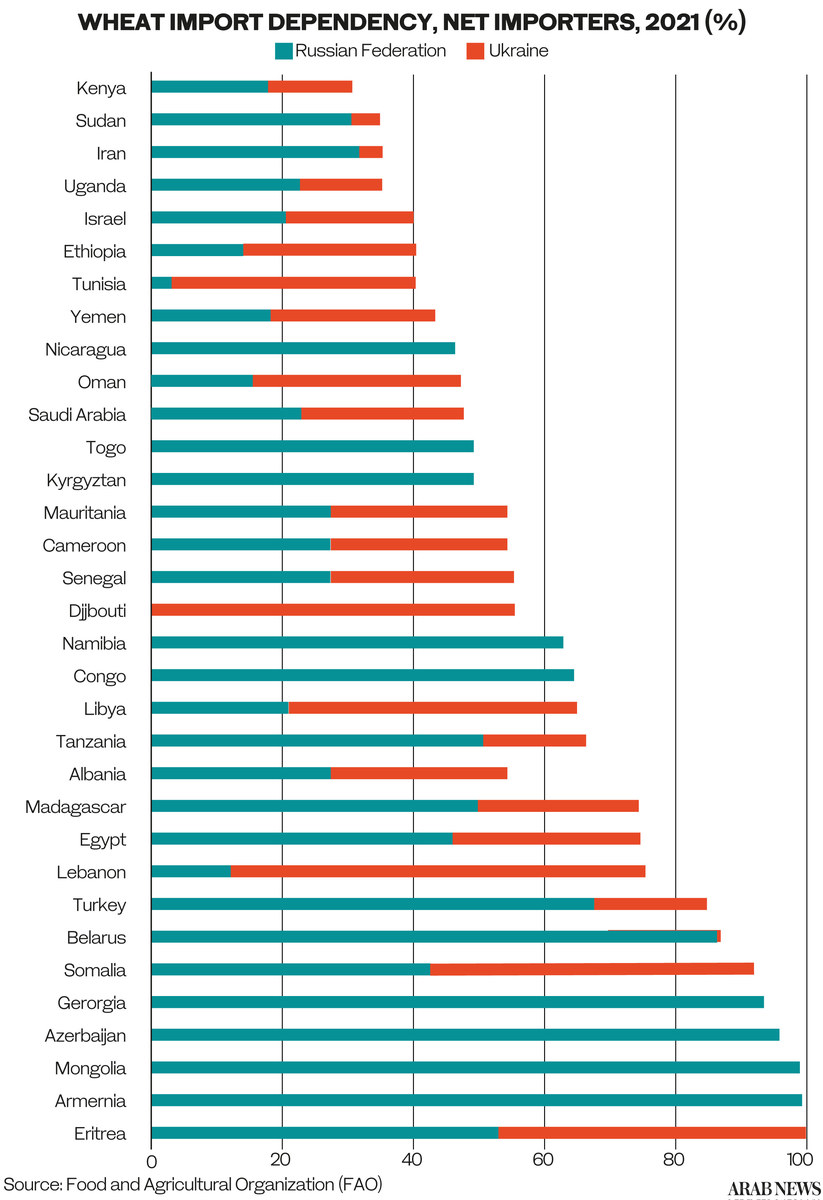

“Countries that are most at risk in the MENA region include Lebanon, Egypt, Yemen, Iran, Libya, and Sudan,” warned Devlin Kuyek, a researcher at GRAIN, which focuses on monitoring and analyzing global agribusiness trends.

The expert who exclusively spoke with Arab News believes that Saudi Arabia and Oman will be impacted to a lesser extent, as they have the means to source elsewhere.

The impact of food supply chain disruptions will depend on each country’s access to imports. “Price is less of an issue for the GCC than supply,” said Kuyek.

However, he underlined that during the food price spike of 2007, the GCC countries struggled to get access to the food they needed, at any given price, as food-producing countries started to block exports in order to control domestic prices.

“Another question worth asking is, will these countries continue to source from Russia?” he pondered.

Russia is still exporting, even if at a lower capacity. Due to their relatively good relations with Moscow, some MENA countries may be able to continue getting grains from Russia.

GCC preserves food security

History shows that when food prices soared in 2007, GCC countries responded to global disruptions by taking certain measures to maintain and protect their food supplies.

“Sovereign wealth funds (in these countries) countered (food price rise) by buying up farmland in Africa and securing more supplies,” said Aliya El-Husseini, senior associate — Equity Research at Arqaam Capital, in an interview with Arab News.

Since then, she said, they started building strategic reserves and local production capacity, which is reflected in the more muted inflation figures this year.

The researcher added that while the GCC still imports nearly 85 percent of its food supplies, it continues to be considered among the most food-secure regions globally.

Food supplies had already started to be disrupted by the COVID pandemic, highlighted El-Husseini.

This prompted at the time regional governments to launch immediate measures to preserve food security, including financial exemptions and credits to farmers and agribusinesses, movement exceptions for agricultural workers during strict lockdowns, and packaging and distribution support, she explained.

“Subsidy regimes in the region have helped maintain inflation for several years, but a lot of subsidies have been phased out since 2016, while some subsidies still remain and are being expanded to help mitigate price hikes,” added El-Husseini.

Saudi Arabia capped local fuel prices last June, she said. This has helped keep the transport inflation in check, but, El-Husseini pointed out that it is not enough to offset the rising prices in the other major categories of the food baskets.

“The partial reversal of the VAT, which was increased from 5 percent to 15 percent on 1 July 2020, in Saudi Arabia, could be one key measure to help further contain prices, as the GCC is running fiscal surpluses, thanks to high oil prices and relatively tight fiscal spending plans,” she emphasized.

Other factors that could help GCC countries weather the food crisis are that they have been outsourcing farming to other countries for years. This ensured that they had more direct control over grain trading companies.

In order to meet their local population demand, the GCC countries have acquired agricultural land in foreign states in Africa and Asia, as well as Arab countries in the Nile Basin, according to a paper titled “Land grabs reexamined: Gulf Arab agro-commodity chains and spaces of extraction” by researcher Christian Henderson.

Yet Kuyek does not seem to view this particular strategy as full proof. “I don’t think the purchase of land in other countries has done much to buffer the GCC demand for imports. Many of the overseas projects collapsed or never got off the ground,” he observed.

Projects that are up and running could also face significant challenges in the form of export bans imposed by foreign countries. Sudan, which is home to a number of GCC mega-farms, is one example where such a scenario could happen.

The GCC countries have nonetheless taken a step further by buying stakes in major food companies.

“Abu Dhabi took a 45-percent stake in Louis Dreyfus last year, and part of the purchase was predicated on prioritizing trade to the UAE,” said Kuyek.

In 2016, Fondomonte California bought 1,790 acres of farmland in California for nearly $32 million. Fondomont’s parent company is none other than Saudi food giant Almarai.

“While we are seeing an upward pressure on price across the region, inflation is unlikely to reach the levels seen in other emerging or developed markets,” concluded El-Husseini of Arqaam Capital.

Noting that the news was copied from another site and all rights reserved to the original source.

xnxx,

xvideos,

porn,

porn,

xnxx,

Phim sex,

mp3 download,

sex 4K,

Straka Pga,

gay teen porn,

Hentai haven,

free Hentai,

xnxx,

xvideos,

porn,

porn,

xnxx,

Phim sex,

mp3 download,

sex 4K,

Straka Pga,

gay teen porn,

Hentai haven,

free Hentai,