EU looks to replace gas from Russia with Nigerian supplies

Follow-ups -eshrag News:

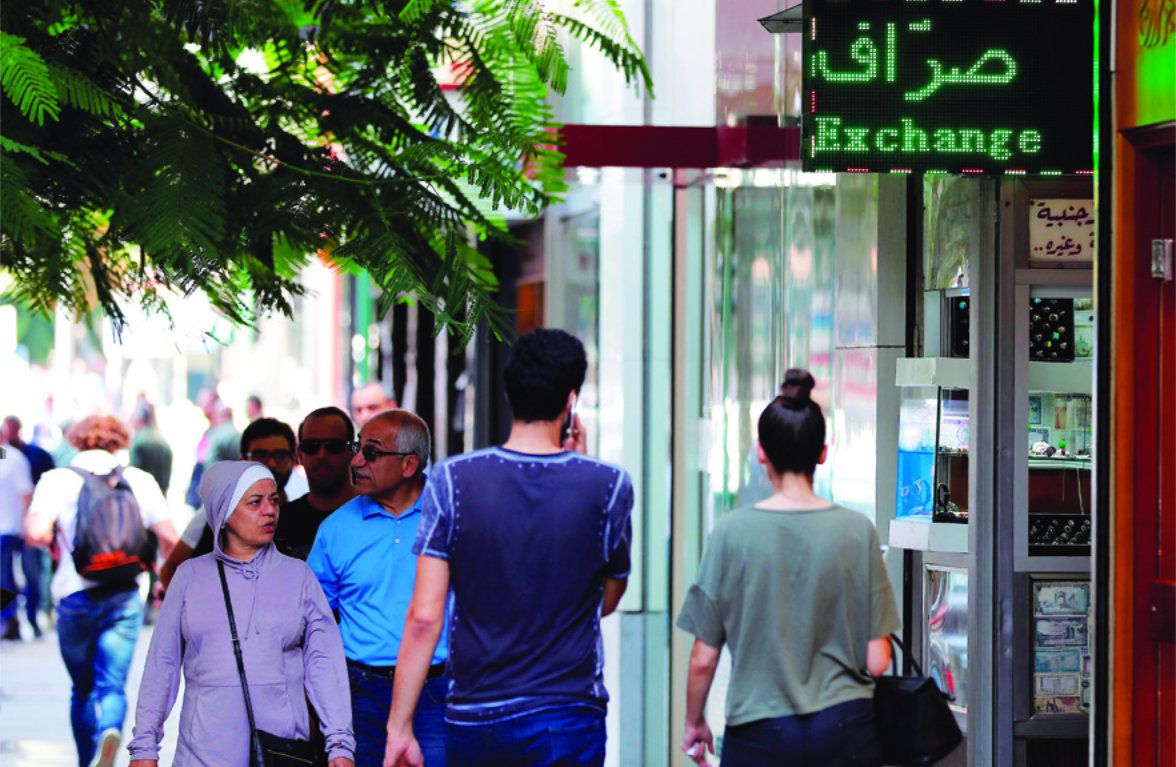

BEIRUT: With their money stuck in banks, the steep devaluation of the Lebanese lira, the de-facto suspension of Circular 331 and the rising inflation, investors and the Lebanese central bank Banque Du Liban have reached an impasse.

“The first five years of Circular 331 initiative were great to the ecosystem, venture capitals included,” Walid Hanna, founder and CEO of Middle East Venture Partners, told Arab News.

The circular released by BDL in late 2013 injected nearly $400 million into the entrepreneurial sector to build a Lebanese knowledge economy.

“The initiative seamlessly empowered the ecosystem until the financial crisis occurred in 2019. Problems happened when venture capitals powered by the circular received capital calls from their banks and the BDL, either in Lebanese liras or US dollars,” said Hanna.

A capital call is a legal right by which a fund manager asks the fund investors or shareholders to pay their pro-rata portion of their fund commitments.

“The devaluation of the lira, which has lost more than 90 percent of its value, made the situation complicated and problematic,” added Hanna.

After local banks decided to withhold the savings of individuals and institutions at the onset of the financial crisis in October 2019, most VCs lost a significant amount of money. Still worse, the banks tethered their startups’ capital.

Another problem was that the VCs received their capital calls — their due money from investors — in Lebanese dollars or “lollars.”

A “lollar” is a US dollar stuck in the Lebanese banking system; in other words, a computer entry with no corresponding tangible currency.

The issue of the “lollar” made it impossible for startups to expand their businesses abroad. The fact that BDL required startups and VCs to not spend any “circular 331 money” outside of Lebanon didn’t help matters, explained Hanna.

“Therefore, it is a triple problem for the banks, the startups and BDL. This is where the decline started,” Hanna concluded.

Stashed sums in the banks

When asked about how much money MEVP had stuck in local banks, Hanna replied that the Impact Fund, MEVP’s Lebanon-based fund, has $ 7 million in the banks. The company launched the fund in 2014 with an initial value of $70 million, most of which was invested in 29 Lebanese startups.

“A number of these startups have already shut down their business in the past three years,” Hanna said dryly.

HIGHLIGHTS

The circular released by Lebanese central bank in late 2013 injected nearly $400 million into the entrepreneurial sector to build a Lebanese knowledge economy.

Another problem was that the VCs received their capital calls — their due money from investors — in Lebanese dollars or ‘lollars.’

A ‘lollar’ is a US dollar stuck in the Lebanese banking system; in other words, a computer entry with no corresponding tangible currency.

While the VC relies on three other regional funds in the Middle East and North Africa to sustain itself and is doing quite well, the current situation in Lebanon has become a thorny problem for them, other investors and fund managers.

“The primary thing that affected us was our lack of ability to disperse money to our startups, most of which are in their early stages,” Fawzi Rahal, managing director at Fla6Labs Beirut, told Arab News. “It also interrupted our capital call and fundraising process.”

Flat6Labs Beirut, which manages a $20 million fund, had plans to launch cycle 5 of its program, which involved investing in 8 to 10 startups. However, the bootcamp was interrupted when the crisis occurred in late 2019 and Rahal and his team could not complete the shortlisting of the startups into cycle 5.

“Of course, later on, we realized that even had we done shortlisting, we wouldn’t have been able to continue with the investments because our capital call was delayed,” said Rahal.

BDL’s restrictions

BDL has prevented all Lebanese startups from relocating abroad, thereby restricting their mobility and access to foreign funding, which led many startups to go bankrupt and halt operations.

BDL also stated that it would not accept startup “exits” to be made in Lebanese liras or “lollars” but wants each startup to “exit” in fresh dollars i.e. to be bought by companies abroad with greenbacks.

“This is ridiculous,” Hanna says scathingly. “We have a country going backward with the GDP contracting in the past three years and reigning inflation, currency devaluation, brain drain and trauma from the Beirut port explosion. Why would anyone invest in Lebanon under such circumstances?”

However, according to a senior investment source who chose to stay anonymous, the central bank has a different point of view.

As part of the then-functional Circular 331, BDL had given a lot of money to the banks, and the banks had invested this money as shareholders or limited partners in the VCs. More importantly, they plowed in the money when the exchange rate for $1 was 1,500 Lebanese liras. Today, it is 25,300 Lebanese liras.

This is one of the reasons why BDL is not accepting startup exits in “lollars” or Lebanese liras and demanding fresh dollars instead.

“Basically, the BDL is asking if we are cheating them of its share. Because that’s how it looks like [to them],” an informed source told Arab News.

He added that to make matters worse, there is no legal difference today between a “lollar” and a dollar in Lebanon.

The “lollar” stuck in banks is legally the same as a fresh dollar “therefore, you cannot take someone to court and ask them to pay your dues in fresh dollars,” the source said.

“And because the law does not differentiate between the two, the law cannot protect you or BDL in this case.”

Breaking the impasse

“I think it is about aligning our interests as fund managers, BDL, the banks and the portfolio companies,” another senior banking source said to Arab News.

“The fund managers and the bank shareholders are aligned in that they both want the best price possible for their exits.”

The source continued to say that, in the absence of follow-on investments and with most funds reaching the end of their five-year investment period, a realistic approach is needed regarding the best exit under the current challenging circumstances.

“The ecosystem requires an update to the current 331 regulatory framework that considers the new challenges, allowing us to escape this deadlock.”

Our source reminded us that “the positive impact of the 331 circular offsets by far the challenges we are facing today.”

Arab News contacted other venture capitals for this piece, such as Berytech, BY Venture Partners and Cedar Mundi but received no response.

Noting that the news was copied from another site and all rights reserved to the original source.

xnxx,

xvideos,

porn,

porn,

xnxx,

Phim sex,

mp3 download,

sex 4K,

Straka Pga,

gay teen porn,

Hentai haven,

free Hentai,

xnxx,

xvideos,

porn,

porn,

xnxx,

Phim sex,

mp3 download,

sex 4K,

Straka Pga,

gay teen porn,

Hentai haven,

free Hentai,